The Penultimate Peril

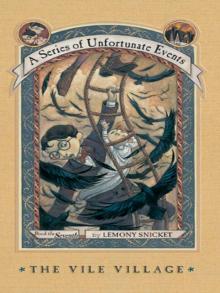

The Penultimate Peril The Vile Village

The Vile Village Who Could That Be at This Hour?

Who Could That Be at This Hour? Shouldn't You Be in School?

Shouldn't You Be in School? Why Is This Night Different From All Other Nights?

Why Is This Night Different From All Other Nights? The Reptile Room

The Reptile Room File Under: 13 Suspicious Incidents (1-6)

File Under: 13 Suspicious Incidents (1-6) The End

The End The Bad Beginning

The Bad Beginning When Did You See Her Last?

When Did You See Her Last? The Miserable Mill

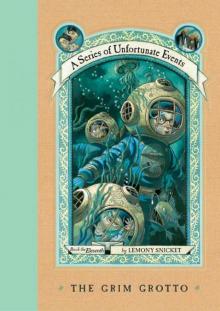

The Miserable Mill The Grim Grotto

The Grim Grotto The Austere Academy

The Austere Academy The Ersatz Elevator

The Ersatz Elevator The Wide Window

The Wide Window The Carnivorous Carnival

The Carnivorous Carnival A Series of Unfortunate Events Box: The Complete Wreck

A Series of Unfortunate Events Box: The Complete Wreck The Slippery Slope

The Slippery Slope Read Something Else

Read Something Else The Carnivorous Carnival asoue-9

The Carnivorous Carnival asoue-9 When Did You See Her Last

When Did You See Her Last The Slippery Slope asoue-10

The Slippery Slope asoue-10 The Hostile Hospital asoue-8

The Hostile Hospital asoue-8 A Series of Unfortunate Events Collection: Books 1-13 with Bonus Material

A Series of Unfortunate Events Collection: Books 1-13 with Bonus Material The End asoue-13

The End asoue-13 File Under

File Under Who Could That Be at This Hour? (All the Wrong Questions)

Who Could That Be at This Hour? (All the Wrong Questions) The Vile Village asoue-7

The Vile Village asoue-7 The Grim Grotto asoue-11

The Grim Grotto asoue-11